-40%

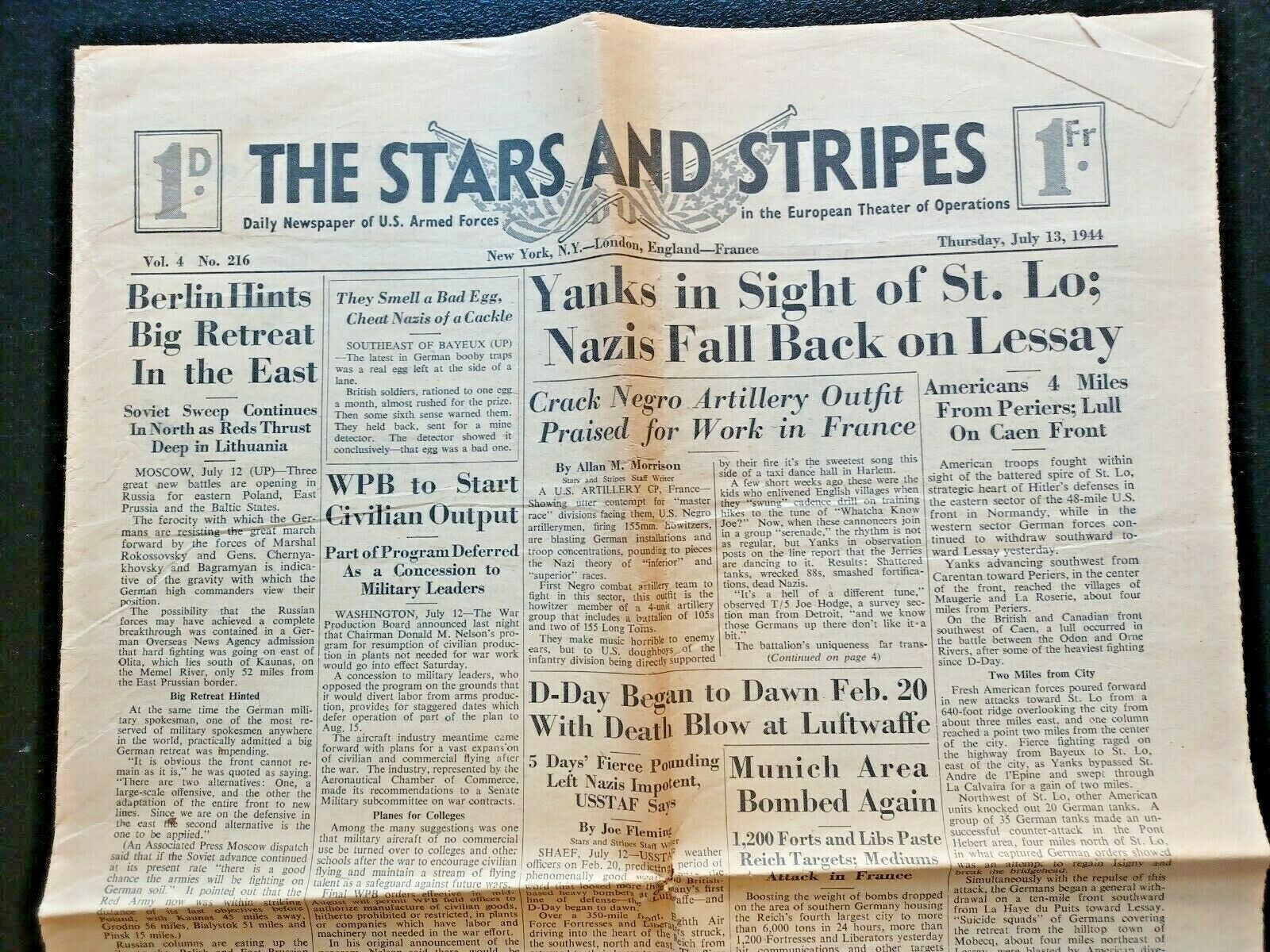

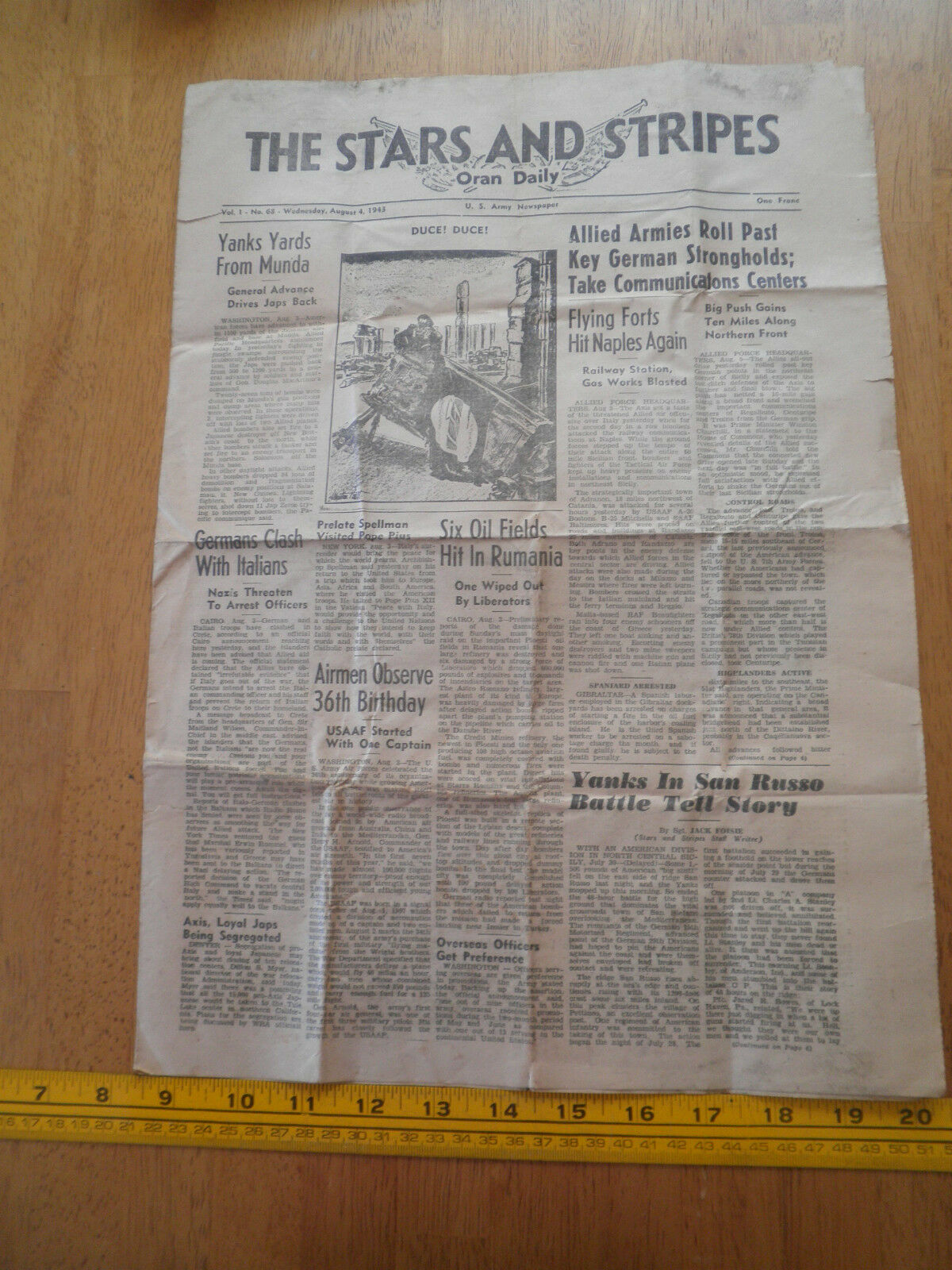

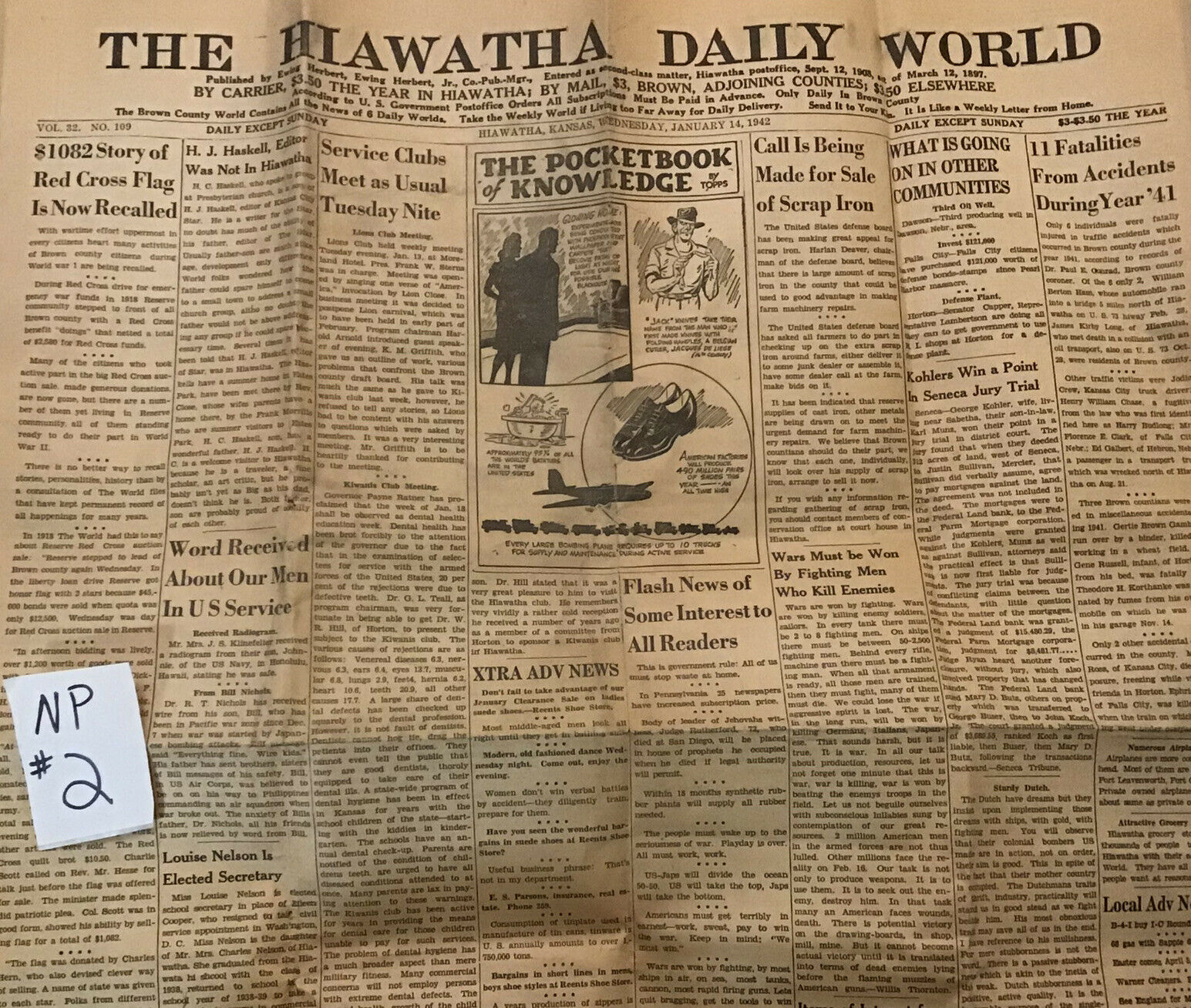

Guinea Gold WW2 WWII Austrailian Newspaper American Edition Dec 31, 1942

$ 10.55

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

Great piece of WW2 history. Some bottom edge damage, corner folds and subtle horizontal folds.Here's a great article that explains the significance of this newspaper.

History Magazine October/November 2015 - GUINEA GOLD: BY AIR, LAND AND SEA

JAMES BREIG LOOKS AT HOW SOLDIERS FROM TWO CONTINENTS MINED GUINEA GOLD FOR NEWS

The front-page headline on the 15 August 1945 issue of a unique wartime newspaper consisted of only two words, printed in all-capital letters that rose two inches: IT’S OVER. Two more words, only slightly smaller, formed the subhead: UNCONDITIONAL SURRENDER. Together, they occupied nearly 30 percent of the page’s space. As they read those four words, thousands of Australian and US servicemen serving on New Guinea breathed a sigh of relief. The Empire of Japan had given up; World War II was over. The medium delivering the good news was Guinea Gold , a daily that brought world news, sports data,light articles and even a beauty contest to those who had battled for freedom, many of them half a world away from their homes.

From 19 November 1942 to 30 June 1946, Guinea Gold kept the members of two continents’ military up-to-date. The four-page daily, which would tally more

than 1,300 issues, was conceived by two Aussies: Reg Leonard,a war correspondent for a Melbourne paper, and Lt. Col.George Fenton, who was in charge of wrangling the newsmen on the world’s second-largest island.

Years later, one of the newspaper’s staffers, Paul Jefferson Wallace, wrote a booklet to preserve the history of Guinea Gold ,which, he said, “brought to the news-hungry men... serving in the steaming jungle topics of interest to allay their boredom and boost their morale.” When Leonard next proposed the idea of the daily to Australian Gen. Thomas Blarney, the latter turned

the journalist into a major who was assigned to “do the bloody thing.”

Wallace said that Blarney, commander of Allied Land Forces in the South West Pacific Area,insisted that the journal “present factual news without comment...He was resolved that the Army newspaper should contain no editorial comment.” The general affirmed that “it is contrary to my policy to use an Army newspaper for propaganda of any kind.” He made that comment in a letter to another key booster of the newspaper - Gen. Douglas MacArthur, supreme commander of US forces in the Southwest Pacific.

Fleeing the Philippines after the Japanese had seized that island early in the war, MacArthur ended up in New Guinea. From there, he directed a series of military moves that would eventually lead to Japan s surrender. Early on, he endorsed the idea of Guinea Golds being sent to American as well as

Australian troops, making the newspaper the only journal during the war to inform soldiers who were serving two nations.

News information on current events ,” MacArthur declared , is “the very breath of modern existence. To the combat soldier , [newspapers] are as

necessary as bread and bullets .” He went a step further by en-

suring that Guinea Gold got scoops on breaking news 20 hours before other media were updated.

Each day’s ration of Guinea Gold was delivered throughout New Guinea, with circulation soaring as more and more units arrived from across the Pacific

and from Australia. At its peak,as many as 64,000 copies were printed seven days a week and delivered to outposts by mail, jeeps, trucks and airplanes. When Italy surrendered to the Allies in 1943, for example, the Associated

Press wrote that “planes, radio and telephones were used in getting the news... to the fighting men of New Guinea... Copies of Guinea Gold... were dropped over the battle fronts from planes, after Army trucks had rushed the papers to various airfields.” Because the free paper was passed from

hand to hand, a guesstimate placed its actual daily readership at 800,000.

In its first issue, the editors of the daily let readers know that

they understood that “troops have come to realize that reliable news

is an important item in any army’s mental diet.... [Our] aim will be

to present news concisely, accurately, without bias.” Recognizing that the four-page Guinea Gold had “rigid space limitations,” the editors promised that “within these limits” would be “as complete coverage of day-to-day news

as possible.” Only rarely did the newspaper add to its daily allotment of four pages, each about the size of a typewriter sheet.

In his account of the paper, Wallace outlined how the contents of Guinea Gold were apportioned: “The front and back pages concentrated on up-to-the-

minute news from around the world, including coverage of major sporting events on the back page. Page 2 was devoted to extracts from Australian and US newspapers published a few days previously, which air transport crews delivered to Guinea Gold .”

Over the course of the war, hundreds of Australians and New Guineans worked on the newspaper. such banner headlines as “Allied Offensive in Sicily Develops Favorably” “Rabaul Raid Lasts Three Hours” “Pulverising Air

Offensive Takes In Pomerania, E. Prussia & Poland” and “250,000 Nazis Falling Back to East Prussia,Moscow Claims”. But there was also room for lesser items: singer A1 Jolson was hospitalized for malaria and pneumonia after a

USO tour of North Africa, for example, and Salvo, a fox terrier,

had become the world’s first“parapup” after making a parachute jump of 1,500 feet in Cleveland and landing safely on all fours. The paper also took pot-

shots aimed at lessening the enemy’s image with such stories as “Fuhrer Has New Girl Friend” and “Captured Nazi General Calls Hitler Tmbecile’”.

At the end of 1943, Time magazine wrote that Guinea Gold 11 never ran pin-ups”, an assessment that was almost correct. A photo of a woman in a bathing suit had appeared in the 20 February issue that year, for example, while acome-hither portrait of actress Dorothy Lamour was published a month afterthe Time article. However, the military newspaper more often carried pictures of women that showed them contributing to the winning of World War II. Here are some examples:

■ A woman in uniform with a caption explaining that she was among 300

members of the Australian Army Medical Women’s Service who had arrived

in New Guinea to serve in hospitals

■ Dorothy Tangney, who was the first woman elected to the Australian Senate

■ Eve Curie, daughter of Madame Curie, who had fled France to serve in the

resistance effort

■ A teenaged Princess Elizabeth (now Queen Elizabeth) in a military uniform

with a caption noting that some people hoped she would be named Princess

of Wales by the king

■ A former ballet dancer, sporting a parachute, who had become the first

woman to fly with RAF bomber pilots as they tested equipment

Perhaps the most touching photo was captioned “Tiny Sufferer”, which ran in the Guinea Gold issue of 7 September 1944. The picture showed a crying child whohad just been pulled from her London home after a German bomb had leveled

it. The girl has her arms wrapped around her rescuer: a female air raid warden in her uniform and helmet.

The back page almost screamed the news that “Red Army fighting in outskirts of Budapest: City Blazing” while whispering “Film actor dead” referring to literal and figurative heavy Laird Cregar. Such juxtaposition was common

for the journal. Additionally, taking advantage of every square inch of the newsprint, many issues featured one-liners atop the front page to remind troops of steps they could take to win the war. “Join in a blitz on general

waste,” read one, while others urged, “Maintain maximum malaria precautions” and “Keep all fires under control.”

Recognizing that soldiers needed distraction as well as information , Wallace

recalled that u the newspaper promoted a c Girl I Left Behind ? contest , [and] 1,700 photos of wives, sweethearts and baby daughters swamped the

editorial office”. Judges were recruited to examine the hundreds of entries and select a winner from each of the two nations that had dispatched

servicemen to New Guinea s jungles, mountains and coasts.

Reaction to the newspaper from Aussies and G.I.s was positive, if only because they had few alternatives, such as miniaturized front pages from hometown papers and clippings mailed by relatives, both arriving weeks

after they had first appeared. One soldier, in a V-mail to his mother

in Virginia, referred to Guinea Gold as “our one and only newspaper”. Without it, he complained, “we have nothing at all to read.”

Another soldier, Lowell Read, wrote to his girl back home to say, “We get a small newspaper called the c Guinea Gold ’ [that] gives a lot of late news.” Joseph Michaelonis,a New Hampshire resident, told his relatives, “Smokes are hard to get, and reading material is also hard to get. We have a little news-

paper called The Guinea Gold which keeps us informed of the world events.”

The readership ranged from men in the foxholes to the Army’s highest-ranking officer. “I just finished reading Guinea Gold (newspaper),” Airman Lyle Young

wrote his wife in Minnesota at the end of 1943. “The news looks encouraging.” Simultaneously,Time magazine reported that MacArthur got his copy “every

morning with his coffee. He and... other readers in the New Guinea battle area think Guinea Gold is the greatest army newspaper in the world.... It is rarely illustrated, never runs c pin-ups.’ Its readers, polled several months

ago, voted for war news first, political news from home second,educational features third.” The paper, Time continued, “is packed, seven days a week, with more than 100 solid news nuggets.”

Additional proof of the popularity of the paper was to be found in how many soldiers sent copies home so that their loved ones could share their reading material. In 1942, for example, Sgt. Rudolph Mohler, an Ohioan, mailed his parents a copy with a vow that “you can expect bigger and better news” of how the US forces were battling the enemy. An Iowa corporal dispatched an issue home in 1943, along with a tiny piece of a Japanese Zero. A 1944 human-interest story in The Chicago Tribune recounted how a lieutenant screamed when he awoke to find a python in bed with him. With tongue in cheek,

the article added that American forces “were comforted recently by a cheery article in c Guinea Gold a military newspaper, explaining that pythons in New

Guinea grow to lengths of 20 feet.”

As the newspaper followed troops in their westward march to expel the Japanese from the island, Guinea Gold became a target for enemy planes and earned the informal nickname of “the world’s most bombed newspaper”. Wal-

lace recalled that “on moonlight nights in the early days, c Guinea

Gold 5 was often interrupted by air raids.” Nevertheless, he added,

“deadlines were still met,” thanks in part to the “selfless and untir-

ing service” supplied by New Guinea natives.

Leonard noted that some staff members “intercepted radio news by matchlight during the bombing raids”. When the electricity went out, he added, “brawny arms provided power for the presses.” Besides being the most-bombed

newspaper, Guinea Gold also became perhaps the war’s most seat-of-the-pants newspaper because the staff often had to ad-lib. At times, for example, a shortage of type led to some being handmade by a New Guinean who carved T’s

out of wood, while the editor fashioned R’s by adding tails to P’s. He got the tails by clipping L’s.The hue of the paper on which the daily was printed varied according to what was available. Surviving copies may be brown from age or from their original tan color. Equipment was begged, borrowed

and maybe even stolen. One time,compliant sailors from a US ship contributed some needed items; it is not known if their captain was aware of the transfer of machine parts from one ally to another.

The most telling example of the paper’s make-do spirit occurred at a key moment. When Japan surrendered and the editor needed a huge headline to trum-

pet the end of the war, an Australian sergeant shaped the celebratory words from a handy chunk of linoleum.

JAMES BREIG ’s most recent book is Star-Spangled Baseball:

True Tales of Flags and Fields. He is also the author of a nonfiction

book about WWII, Searching for Sgt. Bailey: Saluting an Ordinary

Soldier of World War II.